Malcolm X's Hidden Shame

The tragic element in Malcolm X's relationship with his mother.

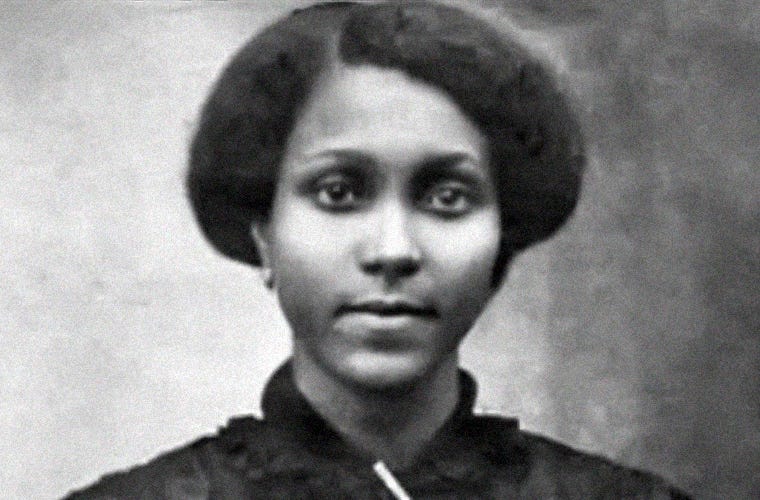

An autobiography purports to an insider view of the hopes, failures, triumphs, and tragedies of the author’s life. But there are parts of ourselves that remain hidden: memories too painful to relive, wounds too raw to share, the residue pain unhealed by the passage of time. The Autobiography of Malcolm X offers a mixed bag in this regard. Malcolm is candid about his regret over his treatment of his teenage girlfriend Laura, and the impact his shameful treatment of her had on her downward spiral into prostitution and drug abuse. But he is far more reserved when speaking about his mother, Louise Little.

Despite myriad public appearances and speeches, Malcolm seldom referred to his mother. Malcolm was notoriously quick with a quip for a journalist and revelled in the attention garnered by his larger-than-life persona. But he would retreat into an uneasy reticence at the mere mention of his mother, unflinchingly noting that he would kill a man who said the wrong thing about her. It was a touchy subject for the National Spokesperson. Though decades had passed, his anger over the white man’s treatment and institutionalisation of his mother had not subsided. But beneath this anger lingered yet another emotion, a sense of guilt at the role he played in his mother’s tragic descent into insanity.

The death of Earl Little in 1931 placed overwhelming financial stress upon the Little household. The insurance company, against all evidence, ruled that Earl’s death was a suicide, and withheld the $10,000 accidental death policy that Louise was entitled to. Without that payment, Louise did her best to maintain their strict routine and the family’s reputation for promoting black independence, refusing government allowances and other external sources of assistance. She resorted to selling hand-made clothes to make ends meet. Her work however, which was inconsistent — she was often fired when employers discovered that she wasn’t white — was insufficient for her family, and her children often went hungry. Indeed, Malcolm notes in the Autobiography that the children were often dizzy due to hunger.

Her resolve to maintain independence eventually withered, and she sought assistance from a Seventh Day Adventist Church, and from government services. Support services not only placed unnecessary hurdles for her to collect the little funds they provided, but also attached conditions. State welfare workers were often condescending, with Malcolm noting:

The state Welfare people . . .acted and looked at her, and at us, and around in our house, in a way that had about it the feeling - at least for me - that we were not people. IN their eyesight we were just things, that was all.

Louise’s mental health took a further nosedive after Edgar Page, with whom she had struck up a relationship, left her after he found out she was pregnant. Although her family and friends were generally supportive of her and her child born out of wedlock, the emotional anguish at Edgar’s rapid departure and the stress of raising a new baby alone worsened her condition.

To alleviate their financial woes, Wilfred dropped out of school in the 11th grade to work full-time as a presser at a local dry cleaner, while Hilda took care of the kids at home. Malcolm and Philbert were notoriously lazy and did little but shirk familial responsibilities and hang out with their teenage friends. But what made their nightly escapades with their friends particularly significant was that they would steal Wilfred’s hard-earned money, as well as their mother’s widow pension and government assistance. The effects of their antics would soon come to the fore.

Wilfred has lost his job in the summer, and left with haste for Boston to find work. He found a decent paying job, and would send $20 every week to his family home to help Louise with the bills. But Louise never received the money.

In the fall, Wilfred received an ominous letter from the McGuires informing him about rumours that his mother might soon be institutionalized. Packing up after payday, the eldest son headed home to Lansing. Upon his arrival, Wilfred immediately discovered that

the cash he'd been mailing regularly throughout the summer had failed to reach its intended destination. His financial assistance had not made things better.

Brothers Malcolm and Philbert, "whichever one got there first, had been stealing the money," Hilda reported to Wilfred. "Once in a while she'd get it." Usually, however, the two blood rivals would race each other to the mailbox, rip open the envelope from Boston addressed to their mother, and brazenly head back into town with the pilfered dollar bills.

The situation was far more perilous than Wilfred had imagined. Louise "was in hell," he discovered firsthand. "It was a pitiful situation because she couldn't make ends meet. Food was a problem, getting from meal to meal." Gone were the chickens, rabbits, the goat, and the cow. The basement, once stocked with canned fruit and vegetables over the winter, was now completely barren. Working with the knowledge Louise had imparted to her children about wild plants, she and Hilda had taken to pulling up edible weeds, roots, wild-growing berries and herbs, in an effort to put meals on the table for the younger kids.

"She had reached a point where she either had to commit suicide or just leave this world one way or the other-by just tuning it out," reported Wilfred. "And that's what she did. She just tuned out everything. She started living in a world of her own, not communicating except when she wanted to. At times she'd be very communicative."

During these final years of the Depression, a two-pound loaf of bread cost fifteen cents. Thus, the money Wilfred was mailing back from Boston could have provided food and made acceptable headway with the expenses. But such marginal relief failed to materialize with his two younger brothers on the prowl. When confronted about the thievery, Philbert, characteristically, denied it. Malcolm shied away from discussing it with his older brother. Each played a significant role in accelerating the family's downward spiral.

Viewing the impending danger of institutionalisation, Wilfred escorted his mother to a private psychiatrist to assess her psychological condition. The doctor confided in Wilfred that Louise did not need to be institutionalised. She was struggling with financial pressures and burden of raising kids alone, but with some nourishment, relaxation, and rest, she would be okay. The family however, lacked the funds to place her in a supportive environment, and in January 1939, Louise Little was diagnosed as insane and taken to Kalamazoo State Hospital against her will. She was kept there for twenty-four years, eventually released in 1963. As Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965, and as such, had 2 years to visit his mother before his early death. Les Payne however, notes that Malcolm never visited her, too riddled with shame:

Similarly, his many childhood betrayals-including his having repeatedly stolen money that could have saved the Little family from severe poverty were cited by his siblings as a factor in their mother's mental breakdown. Malcolm himself blamed "the Welfare [department], the courts, and their doctors" for crushing the family and institutionalizing his mother "as a statistic that didn't have to be." Louise would remain in the mental hospital until 1963, when she was released to live with family. She died in 1991, at the age of ninety- four. Still, the tragic collapse of Louise would remain a touchy matter throughout Malcolm's life. After 1952, he never visited her again.

In his biography of Malcolm X titled Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Manning Marable writes:

Malcolm would rarely visit his mother, and seldom spoke of her: he was deeply ashamed of her illness. The experience etched into him the conviction that all women were, by nature, weak and unreliable. He may also have believed that his mother's love affair and subsequent out-of-wedlock pregnancy were, in some way, a betrayal of his father.

It appears that Marable — as he often does throughout his controversial book — makes assumptions that cannot be validated by corroborating evidence. Shame was the overriding emotion that prevented Malcolm X from visiting his mother. But it appears that it was not his shame over her illness, but rather, his shame over the role that he played in her mental collapse that prevented him from visiting her. It is tragic to think that a man who had no hesitation confronting the world and did blink when faced with the threat of murder could not face the repercussions of the misdemeanours of his teenage self.

This piece is the final in a series on Malcolm X, based on the acclaimed biography The Dead Are Arising by Les and Tamara Payne. I hope that you not only enjoyed reading it, but that it provoked you to think about the role that shame plays in your life. Some questions that came to my mind: Was there a great shame in your life that you kept hidden? How did you overcome it?

Please share you responses to the above in the comments section below!

Great reading! We all are made out of experiences and different pieces, even the most brilliant and brave persons!

Anger and shame are often companions. What a brilliant piece, thank you Ali.